Home > Highlighting JAPAN > Highlighting Japan JANUARY 2013 > The Case for New Inscriptions

Highlighting JAPAN

COVER STORY: WORLD HERITAGE—Windows on Japanese Culture

The Case for New Inscriptions

In January 2012, the Japanese government submitted dossiers on “Mt. Fuji” and “Kamakura, Home of the Samurai” to the UNESCO World Heritage Center as candidates for inscription on the World Heritage List. Toshio Matsubara examines their case.

Mt. Fuji and the torii gate of Fujisan Hongu Sengentaisha Shrine

Credit: YOSHIFUSA HASHIZUME

Mt. Fuji is Japan’s highest mountain (3,776 m), situated nearly at the heart of the country. With its solemn and sacred beauty, it has long been seen as a very special symbol of Japan. Since ancient times, it has also been a divine object of worship. It has been a subject for ukiyo-e woodblock prints, paintings, literature, poetry, theatrical plays and other creative forms. It has inspired many different works of art.

The mountain has not erupted since 1707, but before then there were several major volcanic eruptions, causing serious damage in the surrounding regions.

Wakutamai-ike pond

Credit: YOSHIFUSA HASHIZUME

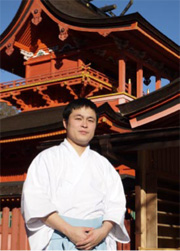

Masafumi Suzuki, a priest of the shrine

Credit: YOSHIFUSA HASHIZUME

Among others, Tokugawa Ieyasu, known for opening the Edo shogunate in the seventeenth century, constructed more than thirty buildings including the Honden inner shrine to overhaul the entire premises. Today, the inner shrine, the Haiden worship hall and the Romon tower gate remain. The inner shrine has been designated by the Japanese government as an important cultural property. Ieyasu further decreed that land located higher than the eighth stage (3,250m) of Mt. Fuji should belong to the shrine. This area remains part of the precincts of the shrine today.

Fujisan Hongu Sengentaisha Shrine

Credit: YOSHIFUSA HASHIZUME

On the basis of the faith in Mt. Fuji, artificial mounds shaped like Mt. Fuji, called Fujizuka, were created in the city of Edo (now Tokyo). Those who were unable to climb Mt. Fuji visited them for worship. Meanwhile, ukiyo-e woodblock prints depicting the sacred mountain gained great popularity. It is said that more than fifty Fujizuka mounds still remain in Tokyo.

“Studies of records in the Edo period suggest that people turned their back on the rising sun while praying on the top of Mt. Fuji (unlike our practice today). At times, their shadows would be cast on the fog and cloud in the crater, and a ring of rainbow light, like the halos of Buddhist statues, appeared around these shadows. At the sight of this phenomenon—known today as the Brocken specter—people in olden days might well have believed that God and Buddha were coming for them,” says Suzuki. “They intently prayed for death and rebirth.”

Tsurugaoka Hachimangu

Kamakura is the place where Japan’s first samurai government was established by Minamoto no Yoritomo to supersede the past aristocratic rule at the end of the twelfth century. This marked the transition from ancient times to the Japanese medieval era. The city has a unique topographical feature as there are mountains on three sides and the sea on one side. They served as natural fortifications. The shogunate made the most of civil engineering techniques at that time to build a distinctive government seat that was different from the ancient capitals of Kyoto and Nara, both of which had been constructed on plains.

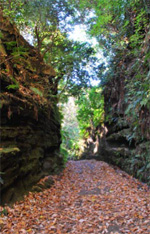

Asahina kiridoshi

As mentioned above, the city of Kamakura is surrounded by mountains on its three sides while its urban area extends in a fan-like form towards the sea. At the position of the rivet of the fan stands Tsurugaoka Hachimangu. As a symbol of the samurai government, the shrine formed a setting of politics and rituals. The city has a total of twenty-one important elements, such as shrines, temples and ruins.

In addition, the samurai culture nurtured in Kamakura is of great historical value. The Kamakura shogunate advocated both Shintoism and Zen Buddhism, which originated from China, in its religious policy. In the middle of the thirteenth century, it started its full-scale efforts to introduce Zen Buddhism. It invigorated trade between Japan and China and positively introduced Chinese culture in addition to Zen Buddhism. Temples in the city grew into places of mental training and academic and cultural learning for samurai. Poetry, literature, calligraphy, paintings, sculptures, the art of tea and others thus spread from Kamakura to the rest of Japan.

The Giant Buddha at Kamakura

Aerial photograph of Kamakura

Kumazawa says, “From the perspective of maintaining the tradition of preserving our city on our own and of preserving it for future generations, the World Heritage inscription is a common goal in our city development. Kamakura attracts 19 million tourists each year and faces several problems such as traffic congestion. To solve these problems, the government and members of the local public are working together towards developing our city into a place deserving the status of a World Heritage site. We see the inscription not as a finish line but as a new start line.”

A park and ride initiative, according to which visitors should park their cars outside the city area and take a bus that carries them into the city, is already underway as a traffic trial. He adds, “If you follow a hiking course that starts at the back of Kenchoji Temple, you will reach the rock called Juo-iwa, where you can enjoy a panoramic view of the city of Kamakura. Stand there and see the landscape unique to Kamakura, with mountains on three sides. That will give you a first-hand insight into what the Home of the Samurai is all about.”

Bringing Tomioka Silk to the World

Tomioka City in Gunma Prefecture is making preparations for the inscription of “Tomioka Silk Mill and Related Industrial Heritage” on the World Heritage List.

Tomioka Silk Mill

Credit: THE JAPAN JOURNAL

The mill played a significant role as the foundation for the development of Japan’s modern industry. Raw silk became the most important export item. At its peak, raw silk covered at least 80% of the total export value, and by the end of the Meiji period, around 1910, Japan was the world’s leading silk exporter. After World War II, the automatic silk-reeling machines developed in Japan and fitted in Tomioka Silk Mill were exported to China and other countries producing silk, encouraging technical exchange through silk.

Tomioka Silk Mill is a very important heritage asset of historical and scientific significance. Moreover, the original premises and main buildings of the mill have been maintained in almost perfect condition. In 2008, the Tomioka Silk Brand Council was established for the purpose of making the silk production system sustainable while supporting sericultural farmers. At the council, those engaged in sericulture and silk processing and sales businesses formed a group to work on developing and selling high quality silk products.

“Raw materials are around 80% responsible for the quality of the silk. Tomioka has both an abundance of water and well-drained soil, which are essential to cultivating mulberry trees and breeding silkworms,” explains Naozumi Hasegawa from the Agriculture Section in the Economic Environment Department of the Tomioka City Government. “And as a result of silkworm breed improvements, Tomioka is capable of producing highest quality silk.”

As part of its activities, the Tomioka Silk Brand Council participated in the Silk Market (Le Marché de Soie) in the French city of Lyon in 2008 and 2009. Tomioka Silk drew attention not just for its quality but also for its original products, such as soap and cosmetics, produced from silk proteins extracted from silk.

“While supporting sericultural farmers, we are striving for World Heritage Site status,” says Hasegawa. “We hope that some day people will see the silk-reeling machines in operation again at the mill. ”

© 2009 Cabinet Office, Government of Japan