Home > Highlighting JAPAN > Highlighting Japan July 2017 > Evolving Traditions

Highlighting JAPAN

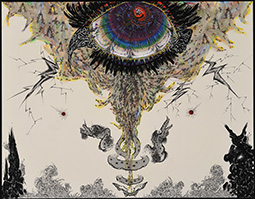

Release of the Divine Spirits

Miwa Komatsu, a young artist whose work depicts the “divine spirits” that dwell within her tradition-loving heart, is drawing the attention of the world.

Japanese artist Miwa Komatsu first captured the public’s interest in 2006, at the age of 22, with the unveiling of her copperplate print “49 Days.” Since then she has been active both at home and abroad, continuing to release works that shine light upon the traditional arts and craftwork of Japan, interpreted in her own unique style.

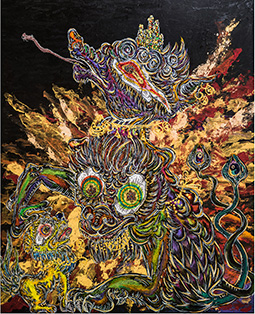

In 2015, her “Guardian Lion Dogs: Heaven and Earth” (a pair of figurines based on the komainu lion-dogs that are traditionally placed at the entrances of Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples in Japan) became a major topic of discussion when they were exhibited as part of a show garden at the British Royal Horticultural Society’s Chelsea Flower Show in the United Kingdom. The figurines were created in a collaboration with the seventh-generation owner of the historic Yazaemon Kiln, producers of Arita porcelain, one of Japan’s most famous and representative varieties of ceramic ware. Komatsu finished her lion-dog figurines in a contemporary style utilizing Edo-period (1603–1867) decorative patterns. In October of that year, the British Museum made the decision to store and exhibit the figurines, applauding their strong and powerful impact, expressiveness and sense of presence. In November, Komatsu was asked to submit another of her works — entitled “Guardian Lion of Historic Ruins” — for auction at Christie’s. The painting sold for a considerable sum of money.

The two themes that appear consistently in Komatsu’s style of artwork are shinju (divine beasts) and prayer. The divine beasts are guardian creatures such as the Sphinx of ancient Egypt or the lions of Mesopotamia or India. In the case of Japan, they are the shishi (sacred guardian lions) that were brought to the country in ancient times together with Buddhism. It is said that over the course of the early Heian period (794–1192), these shishi transformed into the komainu lion-dogs that can still be seen today, at the entrances of many shrines and temples throughout Japan. “Shinju are familiar creatures that connect our human world with the world of the gods,” says Komatsu. By visiting various places around the world to see the divine beasts that represent the origins of Japan’s lion-dogs, and to see people praying, Komatsu says that she has come to value wa, or Japanese harmony, even more greatly.

In 2012, Komatsu participated in Fudo Co., a company that is working to develop traditional Japanese arts and crafts into a global brand under the slogan of “Made in Japan.” Through her participation in this endeavor, Komatsu met various Japanese craftspeople, including the producers of Hakata-ori woven fabrics, Arita porcelain, and long-standing Kyoto-based kimono makers, and accelerated the pace of her collaborations.

From April 2014, Komatsu went to live in the city of Izumo — a place in Shimane Prefecture that is referred to as “the Land of the Gods” — and began working on a piece of artwork themed around the perceptions of the universe and cultural climate that she drew from Izumo Grand Shrine. The following May, she donated the completed work, “Shin Fudoki,” to the shrine. The painting is now on display in the shrine’s Shinkoden treasure hall.

Through these kinds of art-producing activities, the feelings of wa within Komatsu’s heart have become stronger and surer than ever before. The words that she now heralds as her slogan are these: Yamato Power, to the World.

“The essence of yamatojikara — Yamato power — is the ability to mix and unify various different things; the power to combine elements that have been passed down through Japanese tradition, to create something original and unique, and to communicate that to the world once again,” she says.

During her exhibition held in the Akasaka district of Tokyo in June 2017, Komatsu held a live painting session, in which she painted on a canvas in front of an audience of spectators.

Surrounded by over 100 tubes of acrylic paint, Komatsu kneeled before the canvas in a formal seiza position. She meditated to increase her state of mental concentration, before standing up in front of the canvas and beginning to move her brush. She transferred the colors directly from the tubes to the canvas, taking the paint in her hands from a container and throwing it at the canvas surface, before gently stroking it with her hands, making a few strokes with her brush and then adding more colors. The 300-plus spectators who filled the venue breathlessly watched over her every move.

Eventually, Komatsu painted a circle on the floor with radiating lines extending from it. She then proceeded to mix and blend the lines of paint together with both hands, before finally sitting down again in seiza position at the center of the circle and bowing deeply to the audience, thus concluding her hour-long live painting session.

Komatsu is planning further exhibitions in Taiwan (in December–January 2018) and Hong Kong (in February–March). “I think that komainu are the identity of Japan and of wider Asia,” she says.

It may be an exaggeration to say that Komatsu represents the renaissance of modern-day Heisei-period Japan, but at the center of this artist’s heart is the spirit of Japanese harmony, and the massive presence of what she calls Yamato power.

© 2009 Cabinet Office, Government of Japan