Home > Highlighting JAPAN > Highlighting Japan DECEMBER 2012 > Dedicated to Helping Others

Highlighting JAPAN

COVER STORY: Global Messengers—Sharing Japan's Strengths

Dedicated to Helping Others

Countless Japanese people dedicate their lives to work in developing countries, where their skills can have a profound impact on the local communities where they live. This article introduces three such Japanese who have shown their "passion without borders."

Vietnamese physicians and nurses watch an ophthalmologic operation by Dr. Hattori using an endoscope.

Credit: HIROYUKI NAGAOKA

"I can't just stand by and watch people who are on the verge of losing their vision. I want to save their sight if possible using the skills I have," says Dr. Tadashi Hattori. "I only want to see my patients who have regained their vision smile—that's all I want. I have no interest in either money or recognition."

Dr. Hattori is an ophthalmologist who has treated over 10,000 people in Vietnam for free. In Vietnam, there are not enough ophthalmologists or equipment compared to the number of patients. The shortage of ophthalmologists is especially serious in rural regions, and many patients lack access to proper medical care. Dr. Hattori started going to Vietnam after he met a Vietnamese ophthalmologist at an academic meeting in Japan in 2001, who told him, "Many poor patients have lost their sight in Vietnam because they can't get operations, and your excellent skills would save them. Could you please come to Vietnam?" Six months later, in April 2002, Dr. Hattori resigned from the hospital he was working at and started practicing in Vietnam, a country that was completely unknown to him.

People wait to be examined by Dr. Hattori. Many people come from remote villages to have Dr. Hattori examine them.

Credit: HIROYUKI NAGAOKA

Dr. Hattori performs about 800 operations a year in Vietnam, and this is just at local hospitals. He has often conducted more than eighty operations over the course of two days. Patients with cataracts account for most of these in local areas. For economic reasons, more than a few patients come to the hospital after their symptoms have worsened. This makes operations difficult.

"No matter how many operations I do, I never compromise on the quality of each operation," says Dr. Hattori. "I believe the quality of vision with the naked eye is important because Vietnamese do not customarily wear eye-glasses in their daily life."

Dr. Hattori has world-leading skills in vitreoretinal operations using an endoscope. Operations are carried out with an endoscope while a monitor is used to look inside the eye. The work requires patience and precision, but the excellence of Hattori's technique made an American tell him, "With your technique, you could be a millionaire in the United States."

Dr. Tadashi Hattori having lunch at a cafeteria in Vietnam. He aspired to become a physician at the age of sixteen, when his father died of cancer. His father's farewell note to him read, "Take care of your mother. Don't let other people defeat you. Work hard. Live for other people."

Credit: HIROYUKI NAGAOKA

"I have always told young Vietnamese physicians to think of each patient as part of their own family. This prevents them from overtiring themselves while operating, and I can take over in the middle of an operation and avoid complecations," says Dr. Hattori. "I have trained about thirty physicians so far, and I am proud to say that some of them have acquired world-class techniques. And they have started teaching young Vietnamese ophthalmologists. I am very happy about this development."

Help for Dr. Hattori has increased in Japan as well. In 2003, willing volunteers from Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine, from which Dr. Hattori graduated, established the Asian Association for the Prevention of Blindness, and support Hattori's work without compensation. Also, since 2006, Vietnamese ophthalmologist trainees have started being accepted at Japanese hospitals, and about ten have trained in Japan so far. Operation equipment has been provided through the official development assistance (ODA) of the Japanese government. Then, in 2006, a bus equipped with operation and inspection rooms for ophthalmologic treatment was built with financial assistance from Nippon Keidanren (the Japan Business Federation). This bus, which is said to be the only one in the world, was donated to the Vietnamese Institute of Ophthalmology, Hanoi, and is used to treat patients in rural areas far from cities. In recent years, an increasing number of ophthalmologists and students have supported Hattori's work directly as volunteers, visiting Vietnam at their own expense.

"In the future, I want to establish an international medical center that accepts and trains ophthalmologists from Southeast Asian countries," says Dr. Hattori. "That way, we could save even more people throughout Southeast Asia who are about to lose their vision."

|

A Vietnamese Patient of Dr. Hattori Speaks I have had eye problems since childhood. When I met Dr. Hattori at age eighteen, I had already lost vision in my left eye and was only able to faintly sense light with my right eye. I had been unable to attend school since I turned fourteen, and stayed home every day. I was thinking of committing suicide if the operation wasn't a success. My village is far from the hospital, and transportation to the hospital alone costs about five times my father's annual income. But my father found a way to take me to the hospital when he heard that I could get the operation for free this time. Dr. Hattori examined my eyes and discovered that I have proliferative vitreoretinopathy, and he operated on my eyes. Now I can see! I can see my family's faces. I can go out on my own. The ability to see has given me a light of hope that goes beyond just being able to see the things around me. I would like to express my deepest gratitude to Dr. Hattori and all the people in Japan who helped with the treatment costs. |

The wooden boat Kakumeiji (second from left), anchored at port in Zanzibar, Tanzania

Credit: COURTESY OF TSUYOSHI SHIMAOKA

There is a Japanese person who is known as a kakumeiji (a revolutionist) by local people in Zanzibar, an island in the Indian Ocean approximately 20 minutes by plane from Dar es Salaam, the political and economic center of Tanzania, in East Africa. His name is Tsuyoshi Shimaoka and he came to Zanzibar in 1987 to call for a revolution.

"Revolution doesn't only mean removing a government by force," says Shimaoka, "It can also refer to people finding opportunities to work and achieving economic independence."

Tsuyoshi Shimaoka wearing a cloth called kilemba on his head. Shimaoka has been eating just one meal a day for more than thirty years, based on his belief that people should not eat excessively when many people around the world are starving.

Credit: MASATOSHI SAKAMOTO

In 2000, Shimaoka established a trading company in Japan, which imports fair trade Tanzanian instant coffee, called Africafe. Africafe is a brand with a history of more than thirty years and is made of coffee beans that are grown in a region called Bukoba in Tanzania without using pesticides. Shimaoka also sells Tanzanian food such as tea and spices, kanga (colorful African fabric), and miscellaneous products in department stores, a gallery shop in Osaka, Japan and via the Internet.

"After living in Tanzania for many years, I felt it was necessary to change the situation in which people import processed products that use raw materials from Tanzania, such as coffee beans, cotton and cashew nuts, paying prices that are several times higher than the value of the original exports," says Shimaoka. "To achieve that, I thought that we needed to produce products in Tanzania and export them as value-added products to earn foreign currency. That is why I set up a trading company."

Shimaoka gives judo instruction at a facility in Zanzibar

Credit: COURTESY OF TSUYOSHI SHIMAOKA

"The artists were very pleased to see that Japanese people understood their paintings very well," says Shimaoka. "In fact, meeting and communicating with Japanese people boosted their motivation."

Although the business has grown, Shimaoka's lifestyle has not changed. He still lives in the same old public housing estate he inhabited when he first came to Zanzibar. The ships and trucks that he purchased himself are all registered in the names of Tanzanians.

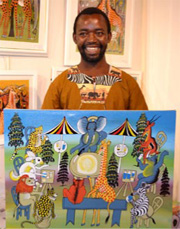

A Tanzanian artist holds his painting at a Tingatinga exhibition in Sapporo, Hokkaido, September 2012.

Credit: COURTESY OF TSUYOSHI SHIMAOKA

Shimaoka became coach for the Tanzanian national judo team, and the team has been taking part in international competitions since 2003. In 2011, the national team achieved a major breakthrough, winning the East Africa Judo Championship 2011. The first students have now started to run their own judo facilities in Zanzibar, and approximately 1,000 students train at seven facilities.

"It is my pleasure to see students, who would never otherwise have had an opportunity to even leave Zanzibar if they had not started judo, gaining broad experience through international competition," says Shimaoka. "Although the Tanzanian team has to date not been able to participate in the Olympics, I believe that it is now strong enough to aim to qualify for the next Games."

Chihiro Shinoda, owner of Kru Khmer; Shinoda was involved in building schools in Afghanistan when she was a student.

Credit: COURTESY OF CHIHIRO SHINODA

Angkor Wat, a World Heritage site in Cambodia, attracts a large number of overseas visitors year round. Nearby Siem Reap boasts many hotels and souvenir shops, and the city is prospering as a base for sightseeing. In the suburbs of Siem Reap, there is a workshop called Kru Khmer, a name that in Khmer means a doctor who practices traditional medical treatment. At the workshop, which is surrounded by a luscious green forest, local women are engaged in mincing and drying herbs, among other tasks. There is a space in the workshop where visitors can purchase herbal products processed on site, including soaps, bath additives, and hand cream.

"These products are particularly popular with Japanese women as kawaii [cute] souvenirs that are unique to Cambodia," says Chihiro Shinoda, owner of Kru Khmer. "I would like visitors to learn about Cambodian traditions through our products."

When Shinoda was a university student, she traveled in Cambodia and was captivated by local people, who seemed to live happily despite their poverty. She then started living in Cambodia in 2008 and worked for a general shop owned by a Japanese manager. While she thought about starting a business that uses agricultural products from Cambodia at that time, she chanced upon a traditional medical treatment being used by a friend who had just given birth. It was called "J'pong," a type of steam sauna that is held in a small tent under which herb-filled water is boiled to make steam to warm the body of the bather. It is believed that this helps women regain strength after giving birth. When Shinoda saw J'pong, she hit upon the idea of starting a business using Cambodian herbs.

"I was always thinking about manufacturing that would do Cambodians proud," says Shinoda. "If herbs were used, it would help increase the incomes of the farmers who grow the herbs."

Chihiro Shinoda (right) with staff cutting herbs at the Kru Kuhmer workshop in Siem Reap, Cambodia

Credit: COURTESY OF CHIHIRO SHINODA

In 2009, Shinoda recruited four Cambodian women from local villages and started Kru Khmer. When the shop first opened, it was very difficult to maintain product quality. Rather than blaming her workers, Shinoda tried to patiently listen to her workers so that they could identify methods to solve the problems themselves. Gradually, the workers began to express their own ideas, and the quality of the products started to improve.

Shinoda has also tried to improve the living standards of her workers. For instance, she has encouraged them to save. Because saving is not a common practice in Cambodia, Shinoda has obliged her workers to put aside part of their salaries. Initially, they were not so positive to save money, but when the mother of one of the workers became sick and this worker could use her savings to help pay for medical care, other workers started to save more seriously.

"When one worker got married and was preparing to leave Siem Reap, I was really happy to hear her talk about her dream of buying a sewing machine and starting a business in her new home," said Shinoda. "I hoped that her experience in our workshop would help her become self-reliant."

In addition to supporting the lives of her workers through Kru Khmer, Shinoda is also trying to support the farmers as much as possible. For example, she purchases herbs from several contracted farmers on a regular basis. She also places orders with female workers in farming villages to manufacture boxes made of coconut leaves, which are used to store the products.

In addition to managing the workshop, Kru Khmer, Shinoda also runs a directly owned shop in Siem Reap, and offers mail order services through the Internet. A local luxury hotel has also started to use Kru Khmer products as amenity goods.

"We have eight employees at present, and I plan to hire two more workers in the future," says Shinoda. "I am aiming to increase production, and sell more products both in Cambodia and overseas."

From left, farmers make boxes from coconut leaves that will be used to store Kru Khmer products; herb farmers contracted to Kru Khmer; handmade soaps mainly made of coconut oil and palm oil; Kru Khmer sells products, such as bath salts using natural salt, herbal bath agents and hand cream among other products.

Credit: COURTESY OF CHIHIRO SHINODA

© 2009 Cabinet Office, Government of Japan