Home > Highlighting JAPAN > Highlighting Japan FEBRUARY 2013 > In the Depth of Winter…

Highlighting JAPAN

COVER STORY: WINTER WONDERLAND

In the Depth of Winter…

Villages within the mountains of the Tohoku, Joshinetsu and Chubu regions of Honshu are hit with heavy snow during the winter. The people living in these villages have come up with their own ideas for houses, tools, clothing, food and various other aspects of life to overcome the winter snow and cold. The crystals of ancestral wisdom and technique born of such a harsh winter climate live on within the people's lives today. Masaki Yamada and the Japan Journal's Osamu Sawaji report.

Gassho-zukuri houses in Shirakawa-go, Gifu Prefecture

Credit: MASATOSHI SAKAMOTO

The gassho-zukuri village of Shirakawa-go (Gifu Prefecture) receives some of the heaviest snow in Japan. Snow accumulates up to two meters high during the snowy season from late-December to early March, and in the days before roads were made for automobile traffic, snow blocked off any transportation route and the area was referred to as an "inland island."

Born of such harsh climatic culture and isolation some 300 years ago was the idea of the gassho-zukuri house. This style is characterized and immediately defined by its uniquely shaped roof. The huge, thatched roof with a grading of 50–60 degrees is a symbolic architectural style through which the traditions of the Shirakawa-go village are passed down to this day.

"There are largely two reasons our ancestors made roofs in this shape," explains Masahito Wada, director of folklore museum Wada-ke (Wada House), which itself is a gassho-zukuri house in which he lives. "One is that by grading the roof sharply, they kept snow from piling heavily on the roof and alleviated the work of shoveling it off. The other is that by making the roof high and large, they were able to obtain a two- or three-layer open space in the attic."

The Wada House attic was used as a sericulture workshop. Its roof is held in place with strong ropes.

Credit: MASATOSHI SAKAMOTO

"The gassho-zukuri house was extremely functional architecture, providing its first floor as a living space, second and third floors as a cocoon-producing factory, and the basement as a production plant for ensho," Wada says.

A gassho-zukuri house also consisted of numerous architectural concepts. For example, its roof is assembled without using a single nail and is held in place with strong ropes. This keeps the roof flexible, which disperses the force of accumulated snow, typhoons or earthquakes by letting the roof slightly shake, and heightens the house's durability.

Masahito Wada lights a fire in the Wada House irori.

Credit: MASATOSHI SAKAMOTO

Today in Shirakawa-go there are fifty-four gassho-zukuri houses. The Wada House is the largest. The Wada clan served as village headmen and guard officials while making a fortune on production and transaction of ensho. As mentioned earlier, the house is now a folklore museum and a must-see tourist attraction in Shirakawa-go.

"There used to be less automobile traffic than we have now, so when I was a child I used to make snowmen and kamakura (snow houses) or go sledding and play to my heart's content in the snow," Wada says. "By finding all these fun things to do, we were able to get through the harsh winter in Shirakawa-go."

Since the village was inscribed on UNESCO's World Heritage list in 1995, tourists to Shirakawa-go have increased, reaching approximately 1.3 million, including many from abroad.

"Winter is when we have the fewest visitors, which in turn keeps the village in a still silence and can probably show what Shirakawa-go really feels like," Wada explains.

Craftsmen hold samples of their Okuaizu amikumi-zaiku products.

Credit: MASATOSHI SAKAMOTO

On a January day, the Seikatsu Kogeikan in Mishima-machi, Fukushima Prefecture held a "Winter Craftwork Class." Snow around the Kogeikan had risen to over a meter in height and the temperature was below freezing, yet about forty people in their thirties to seventies gathered here to work on the region's traditional craft, Okuaizu amikumi-zaiku.

"I was happy today that we had newcomers participate in addition to the experienced folks," comments Shuko Baba, chairperson of the Okuaizu-Mishima Amikumi Products Promotion Council. "The experienced folks including myself usually make products at home, but it's very stimulating to see other people's works like this."

Mishima-machi in Fukushima Prefecture is situated in an area of the prefecture known as Okuaizu, of which about 90% is forest. In Okuaizu, where snow reaches one to two meters in height in the winter, production of amikumi-zaiku using trees and plants has been popular since long ago, and baskets and other amikumi-zaiku have even been found from ruins dating back to 2,500 years ago.

Okuaizu amikumi-zaiku weaving techniques as seen at Seikatsu Kogeikan in Mishima-machi, Fukushima Prefecture

Credit: MASATOSHI SAKAMOTO

Okuaizu amikumi-zaiku is largely classified into three types based on the material used. First is the type that uses the bark of the yamabudo (crimson glory) vine. This bark is extremely strong, so it is often made into baskets that carry heavy loads or knives. It is characterized by its turning into a dark brown color and taking on a unique gloss the more it is used. The type that uses the stem of the silver vine has elasticity and is water repellent, so it is primarily made into sieves. A kan-zarashi procedure of putting the product out in the open winter air at the final stages of production bleaches the product and gives it greater strength. And the type that uses a perennial plant called hiroro is woven with hiroro rope for warp and material such as mowada (bark of broad-leaved deciduous tree called the Japanese lime) for weft. It finishes like lacework and has the flexibility of cotton, and is suitable for handbags and small pouches.

"I usually spend about five hours a day completely engrossed in my craft," Baba says. "I also teach the craft to my grandchildren in Tokyo whenever they come to my home. They take what they made to school and show them off."

These kinds of woven crafts using natural materials were once made all over Japan, but with the spread of industrial products they gradually lost ground. One of the biggest reasons why weave crafting has been passed down to this day here in Mishima-machi is that it began town-wide action to preserve traditional ami-zaiku and train successors in the early 1980s. Basing its operations at the Seikatsu Kogeikan that completed in 1986, the town produced ami-zaiku in contemporary designs and held ami-zaiku classes for its citizens, and the Okuaizu amikumi-zaiku gradually began gaining nationwide recognition. Around 2000, increasing numbers of people wanted to buy Okuaizu amikumi-zaiku, so the craftsmen established the Okuaizu-Mishima Amikumi Products Promotion Council and began selling their works. Today the system allows the craftsperson to receive 80% of the sale price of the work. Some 100 people, mostly in their seventies, make ami-zaiku, with many of them starting the craft after retiring from their business careers. They do not make items to order, but rather make what they want.

Okuaizu amikumi-zaiku has been gaining nationwide popularity over the past several years. The number of handmade ami-zaiku items using natural materials is limited to 600–800 per year, and works can only be purchased (principally) at the Seikatsu Kogeikan. Yet an event held in Mishima-machi three times a year enables sales of ami-zaiku of Okuaizu and from around the nation, and visitors are increasing each year. An event held last early summer drew the largest crowd of about 25,000 in two days to Mishima-machi, which only has a population of about 1,900. "It's a happy moment to see our work sell. We gain a sense of joy that we were recognized," Baba says. "I'm hoping to let more people know about the wonders of Mishima-machi through ami-zaiku."

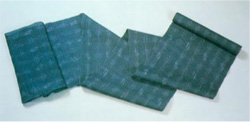

Echigo-jofu fabric is light and well suited to the summer kimono

Credit: COURTESY OF THE ASSOCIATION FOR THE CONSERVATION OF TECHNIQUES FOR OJIYA-CHIJIMI-FU, ECHIGO-JOFU

"Yuki wa chijimi no oya to iubeshi." (Chijimi is a gift of the snow.)

This quote comes from Hokuetsu seppu, which tells about the snow-related nature, life and industries of Echigo (now Niigata Prefecture) in the late-Edo period (1603–1867). Chijimi here refers to Echigo chijimi (Echigo crepe cloth). Today, Echigo chijimi is classified into Ojiya-chijimi and Echigo-jofu depending on the region in which it is produced. Ojiya-chijimi is produced in Ojiya, Niigata, and is hemp textile with a rough surface called shibo, while Echigo-jofu is made in Minami Uonuma, Niigata, and is a plain-woven hemp textile. Both textiles are extremely thin and lightweight, and because they are dry on the skin even in the humid summer season, people have used them as materials for quality kimonos for the summer.

The history of Ojiya-chijimi and Echigo-jofu dates back over 1,200 years. With some records indicating they were offered as gifts to the imperial court or shogun, since long ago they have been highly regarded for their quality. Chosen as a material for the shogunate's ceremonial clothing during the Edo period, they were produced using as much as 200,000 tan (1 tan is 37 cm wide and 12.5 m long and can make a single kimono) a year.

Yuki-zarashi takes place on a sunny day with good weather for the purpose of bleaching the fabric.

Credit: COURTESY OF THE ASSOCIATION FOR THE CONSERVATION OF TECHNIQUES FOR OJIYA-CHIJIMI-FU, ECHIGO-JOFU

"Because of the snow, people of this region were unable to farm outside in the winter. Making Ojiya-chijimi and Echigo-jofu at home in the winter was a valuable source of cash income for the people during the agricultural offseason," explains Masayoshi Ogawa, chairman of the Association for the Conservation of Techniques for Ojiya-chijimi-fu, Echigo-jofu. "Hemp thread breaks easily when the air is dry. The fact that this region is surrounded by snow and maintains just the right humidity made it suitable for hemp production."

Yuki-zarashi is carried out on on fine, sunny days for the purpose of bleaching the fabric. The process can take anywhere from two days to a week, depending on the fabric color and the weather.

Credit: COURTESY OF THE ASSOCIATION FOR THE CONSERVATION OF TECHNIQUES FOR OJIYA-CHIJIMI-FU, ECHIGO-JOFU

"By laying the fabric out on the snow, the fabric not only softens but also turns white. They say that when snow melts in solar heat and the moisture passes through the fabric pores and then evaporates, it releases ozone, which bleaches the fabric," Ogawa says. "When and how long the fabric stays out in the snow depends on the intuition of the craftspeople specializing in yuki-zarashi."

Women primarily take on the role of producing Ojiya-chijimi and Echigo-jofu, and the techniques have been passed down from one generation to the next, from mother to daughter or mother-in-law to wife. Yet with the spread of western clothing after World War II and a decline in demand for kimono, the number of craftspeople with the production technique fell dramatically. To preserve the traditional techniques, the Association for the Conservation of Techniques for Ojiya-chijimi-fu, Echigo-jofu was established and, with assistance from the national and local governments, has trained successors since 1973. It hosts seminars every year for this purpose, in which students split into oumi, kasuri or ori (weaving) courses. Students on the ori course learn the techniques over a period of 100 days, while students on the oumi and kasuri courses learn over 20 days in the winter season, over a span of three to five years. Once they finish the course they are able to work at the local textile manufacturer. Students of ori course are mostly women in their twenties and thirties, with 60% coming from outside Niigata Prefecture. Today there are about seventy Ojiya-chijimi and Echigo-jofu craftspeople, with most of the ori experts being graduates of the association's seminar.

"Students are all extremely passionate, and hardly any of them quit in the midst of their studies," Ogawa says. "We hope to train these people with care and pass the technique onto the next generation."

Fermented Food of the North

Takeo Koizumi, emeritus professor at Tokyo University of Agriculture, enjoys some nishin-zuke (pickled herring), a fermented food of Aomori Prefecture

Narezushi of mackerel, fermented in rice

You eat and study fermented food from around the world. What are the characteristics of fermented food in Japan?

Dr. Takeo Koizumi: One major characteristic is that Japan has so many types of fermented food. Miso, soy sauce, sake, natto (soy beans) and katsuobushi (dry bonito) are Japan's most famous fermented foods. Europe has its own fermented foods in yogurt and cheese, and Asia has baijiu (China), nuoc mam (Vietnam), and nam pla (Thailand), yet no single country other than Japan has so many types of fermented foods. The number of such foods is so high because the country is humid and the conditions are suited to reproducing microorganisms that ferment food materials. Since Japan also has abundant food materials such as fish, vegetables and grains, there are naturally more types of fermented food.

Fermenting food makes it capable of being stored for long periods of time. In the days when there were no refrigerators, fermentation was necessary to preserve food. The Japanese eat a great deal of fish, so there are numerous fermented foods using fish. Well-known examples are shiokara made of cut squid and its intestines salted and fermented, and narezushi made of fish pickled and fermented together with rice.

Tsukemono vegetables pickled in a tsukedoko filled with miso

The Tohoku region in northeast Japan has a particularly wide variety of fermented food. Why is that?

One reason is its harsh winter climate. Since people could not harvest farmed products in the winter because of the cold and snow, they made fermented foods that could be preserved for cold months. They have a particularly wide variety of tsukemono (pickles). They pickled vegetables such as daikon radish, cucumber, Chinese cabbage and eggplant in a tsukedoko (bed) of miso, soy sauce and koji (rice malt). Vegetable tsukemono not only contained abundant vitamins made by microorganisms but was also full of fiber and extremely healthy. Tohoku was traditionally an agricultural region. People sweat from farm work in the summer and lose salt. Tsukemono contains a great deal of salt that replenishes people's supply. The people of Tohoku needed fermented food in order to survive.

The popular and traditional health food that is natto, fermented soy beans

What other fermented foods do the people of Tohoku frequently eat?

They eat natto, made by fermenting soybeans. Among the prefectures with the largest consumption of natto in Japan are Fukushima (number one), Akita (two) and Yamagata (four)—all in the Tohoku region. Today, the people of Tohoku commonly eat natto on rice as do people of other areas, but during and before the Meiji period (1868–1912), they ate it in their miso soup. Since the Nara period (710–794), the Tohoku farmers grew rice in the fields and soybeans on the ridges between them. The people of Tohoku put tofu in their miso soup together with natto. Tofu and miso are also made of soybeans. Prior to the Meiji period, the Japanese people, including those of Tohoku, ate scarcely any meat, but soybeans have as much protein as meat. People were thus able to obtain plenty of protein from miso soup, natto and tofu without having to eat meat, which is why the people of Tohoku were able to build stamina to get through the cold winter.

Iburigakko, a dish of daikon radish smoked in salted rice bran that is popular in Akita Prefecture. Iburi means to smoke; gakko refers to pickles.

Are there any fermented foods of Tohoku that you would like people of the world to try?

Many fermented food products have a unique smell and taste and may not suit the palates of people overseas who are not used to them. But I think iburigakko of Akita Prefecture is one food that anyone can eat and enjoy. Iburigakko is daikon pickled in nukazuke (salted rice bran) and smoked with wood. There are many food products around the world that are smoked; such as coffee, whisky and ham. Yet iburigakko is the only food in the world that smokes fermented pickles. As with smoked food of other countries, iburigakko smells of wood smoke, which is why I believe people of other nationalities would have no problem eating it.

The Tohoku region and Japan have such an abundance of fermented foods. Expo Milan 2015, themed "Feeding the Planet, Energy for Life," will take place in May–October 2015, and I will help introduce Japanese fermented foods. I am hoping to take this opportunity to have people of the world taste the wonders of these foods.

© 2009 Cabinet Office, Government of Japan