Home > Highlighting JAPAN >Highlighting Japan March 2015> Japanese Abroad

Highlighting JAPAN

Home Away From Home

Kominka Makeovers

Karl Bengs Reimagines

Old Japanese Homes for the Modern Era

Against the combined trends of depopulation in rural areas and a preference for more comfortable residences, traditional homes are gradually disappearing from Japan’s neighborhoods. Architect and longtime Japan resident Karl Bengs, however, provides a new option, preserving the essence of these kominka while refurbishing them for the modern era, often with a European flair.

The German native credits his interest in Japan to the influence of his father, a painter doing restoration work in Berlin, as well as Bruno Tout, another German architect with a deep appreciation for Japanese architecture. In his main line of business, Bengs was disassembling old Japanese structures such as teahouses and reconstructing them in Germany. It was through this work that he found his current home in the small village of Takedokoro in Niigata Prefecture. The old house was in shambles, but Bengs says he fell in love right away. He later moved to Japan and rebuilt the place, going on to either restore or build a total of seven homes in the little village as part of his new business.

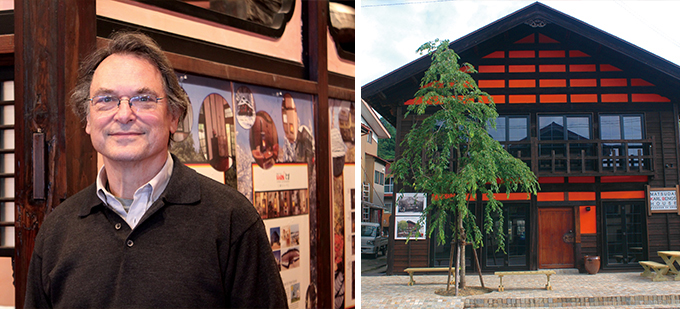

Karl Bengs & Associates is now headquartered in Niigata Prefecture’s Matsudai, occupying a former ryokan (Japanese inn) built in the Meiji Period. Unlike urban offices where space is often limited, this place is airy and spacious, serving in effect as a showroom for his design concepts. Downstairs, a cocktail bar with open seats on wooden floors serves as an event space, while upstairs Bengs has mixed glass-hinged panels and thick, sliding wooden doors with intricate iron fittings taken from an old storehouse slated for destruction.

Bengs understands that many Japanese do not want to live in old residences like these because they tend to be cold and dark, particularly during the long winters in Japan’s snow country. His approach is to make them cozy and comfortable, with floor heating, double-paned windows and insulation to keep the warmth inside. He even mixes elements of German architectural tradition outside and inside to create a fusion of styles. Yet in all of his transformed homes, Bengs says, “The most important point is to keep the framework intact.”

That makes great sense, because the strong, solid, wooden frameworks of Japan’s kominka are not only gorgeous to behold, they also make these traditional homes resistant to natural disasters, including typhoons and earthquakes. “They are built soundly and in such a way that they are easier to fix if damaged by such disasters,” Bengs explains. “Carpenters didn’t use any kinds of nails in their beautiful joinery, which makes kominka flexible enough to withstand the power of nature.”

Despite the aforementioned trend of Japanese avoiding old residences, Bengs believes a surprising number of younger city folk are interested in a less stressful life in the countryside. “They don’t have this fear of snow, or a negative image of countryside life,” he observes. Nevertheless, Bengs admits that one of the challenges for potential homeowners in the countryside is finding jobs, and tells how he has sometimes disassembled country homes and relocated them closer to bigger cities, such as in Tokyo’s Takanawa district, or the suburban side of Saitama Prefecture where there are more job opportunities.

Although Bengs has spent twenty-one years of his life in Japan and has completed fifty residences as of 2015, he says he wants to build another fifty more, and bring other projects to fruition.

“I’d like to preserve the community of architects and carpenters,” he explains, “because they need to have chances to use their skill.” Bengs believes his work is not only about preserving Japan’s kominka, but the skills required to build and maintain them

as well.

© 2009 Cabinet Office, Government of Japan