Home > Highlighting JAPAN >Highlighting Japan August 2015> Delectable Journeys

Highlighting JAPAN

Delectable Journeys

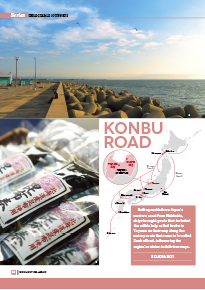

Konbu Road

Sailing south down Japan’s western coast from Hokkaido, ships brought goods that included the edible kelp called konbu to Toyama on their way along the watery route that came to be called Konbu Road, influencing the region’s cuisine in delicious ways.

In the days when kitamae-bune (bune is Japanese for ship, and kitamae is said to have been a term for the Sea of Japan) swarmed the coasts of the country, konbu, a type of edible kelp, was brought down from Hokkaido in great quantities and did much to shape each region’s food culture. Although some three hundred years have passed, that legacy remains strong, and the sea routes used to carry konbu down from the north are known as Konbu Road.

The western branch of Konbu Road ran along the Sea of Japan to routes connecting to Osaka and Kyushu, while the eastern branch plied the Pacific toward Edo (present-day Tokyo). In Toyama Prefecture, a key stop on the road facing the Sea of Japan, residents eat three times more konbu per capita than any other prefecture in Japan. Konbu is also the main ingredient used in dashi soup stock rather than the katsuobushi (skipjack tuna flakes) so ubiquitous on the eastern side of Japan.

Konbu is harvested in many varieties in the summer in the shallow seas around Hokkaido. Long curls of green sway gently just under the surface, and when the time is right (around two years of growth) strong-armed fisherfolk trawl the sea beds like the Greek god Triton, wielding their pronged staffs, thrusting them into the surf with a twist and hauling up their briny treasures. From there the kelp is dried in the open air under the sun on the shore, just as it has been for centuries, and shipped down south.

Konbu is used in a variety of preparations, from soup stock to tea to kobujime—konbu layered with sashimi. Toshiro Makino of Kanemitsu, a company that specializes in producing kobujime for home consumption, explains that the konbu and the sashimi work in a kind of symbiosis, with the salt from the konbu infusing the sashimi and creating a deep umami (savory) taste, and the moisture from the fish bringing out the flavor of the konbu. Makino describes konbu as having umami, sweetness and saltiness as well. That all settles into the fish, creating a dish that with just two ingredients is more than the sum of its parts. Makino touts the health and vitamin benefits of kobujime. “If you eat just konbu and sashimi, that’s enough. You don’t need anything else.”

Those wanting to sample the delicacy in a restaurant can find it not far from Toyama Station. “There’s a strong connection between Hokkaido and Toyama,” says Shinichiro Uji, proprietor of Kaze no Kitamae-ya, a restaurant specializing in kobujime and other Toyama regional specialties. The connection is evident in his shop’s name and the blending of Hokkaido-born konbu and local seafood. His kobujime selection offers seven to ten varieties of seafood depending on the season, and is the special favorite of visitors coming from outside the prefecture that want to savor Toyama flavors. The effect of layering sashimi with konbu boosts the sweetness of the fish and deepens its flavor so it no longer tastes so raw. Other local favorites include hotate (scallops) and salmon, as well as a house-original shochu and a konbu-infused shochu made in Hokkaido to drink alongside them.

Aimono Konbu in Kurobe City specializes in konbu for cooking, such as in soup stocks or sauces. Although Aimono offers over half a dozen varieties, its top seller is Rausu konbu, which is collected near the town of Rausu in northeastern Hokkaido. Prized for its milder, softer character, Rausu konbu is possibly the most sought-after konbu in the world. And konbu is catching on not only in Japanese cuisine, where it’s a staple, but internationally as well: Naoyuki Aimono, president of Aimono Konbu, sends sixty kilograms of konbu per month to Noma, the Danish eatery that has been named the world’s best restaurant on more than one occasion. “Konbu equals umami,” he says, and the world’s foodies know that umami is crucial to excellent food.

In addition to konbu for soup stock (Aimono suggests scoring the edges of the stock piece so it releases more of its tasty properties), Aimono Konbu also makes tororo konbu, a finely shaven konbu resembling gossamer that in Toyama is commonly wrapped around onigiri, or rice balls, instead of the usual sheets of nori (dried seaweed). Aimono’s konbu tea is a salty, savory mouthful, more like broth, with a few squares of the stuff floating at the bottom. “You can eat that too,” says Aimono, and a nibble reveals a briny, slippery bite with an underlying taste of greens.

Those interested in shipping history might visit the Mori-ke, the House of Mori, a well-preserved, nearly 140-year-old house belonging to a family of Meiji Period shipping magnates. Shotaro Mori owned ten kitamae-bune, the largest being a rice-hauling junk of about 150 tons that required around a dozen crewmembers. The house shows how a wealthy merchant of the time lived, as well as some records, shipping routes and model ships that evoke the Mori family’s business.

Though konbu was one of the major products working its way from north to south, the ships also carried a variety of other goods both ways, from Hokkaido in the north all the way to what was called Satsuma Province, at the southern tip of Kyushu. The ships carried news and culture, and Toyama exported rice to other parts of the country.

Another major import/export in the region transported on the ships was medicine from Toyama. The prefecture has been known for what would be called herbal medicine or alternative medicine since the Edo Era. Toyama’s medicine makers depended on the kitamae-bune to import raw materials from all over Japan—and from overseas as well, via Nagasaki. The prepared medicines were dispatched via Konbu Road to distant regions.

The medicines and the traditional medicine makers can still be found in Toyama in establishments like Ikedaya Yasube Shoten, a handsome old business that still uses the traditional ways, importing herbs from around the world, consulting with individual customers about their ailments, and expertly mixing up tailored medicines by hand. The reputation of Toyama as a medicine capital is still strong, says company president Yasutaka Ikeda, with over seventy medicine-related companies still operating in Toyama. The success of the Toyama medicine scene was thanks in part to the kitamae-bune and Konbu Road.

Toyama Prefecture’s development has moved hand in hand with the history of Konbu Road. When asked to describe the flavor of konbu, Kanemitsu’s Makino was hard pressed to come up with an answer. “Konbu is konbu,” he says simply. Here in Toyama, it needs no other descriptor. Everyone knows konbu. For the people of the region, eating konbu is a deeply ingrained way of life.

© 2009 Cabinet Office, Government of Japan