Home > Highlighting JAPAN > Highlighting Japan April 2017 > The New Age of Rail

Highlighting JAPAN

Murder on the Limited Express

Japanese mystery story writers have long enjoyed using railways and trains in their novels.

In Japan, translations of Western detective stories began to be published during the Meiji period (1868–1912). Influenced by this trend, Japanese writers began to write their own mysteries. In the Taisho period (1912–1926), numerous mystery stories revolving around railways were published. For example, Ichimai no kippu (One Train Ticket), which was published in 1923 by the great detective story writer Edogawa Rampo (a pen name derived from the American writer Edgar Allan Poe) (1894–1965), was a short novel about a woman who was killed in a train accident. This was a major novel in the early stage of Japanese train mystery stories. Subsequently, many train mystery stories were produced in parallel with the development of Japanese railways and many writers enjoyed publishing such stories, especially after World War II.

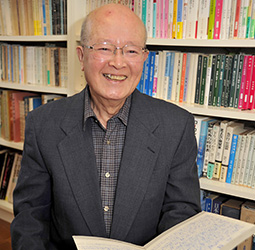

“Mysteries and trains are a very good match. Trains, with their tightly closed compartment spaces, timetables and station buildings are a treasure trove of plot devices,” says railway journalist Takayuki Haraguchi. Haraguchi published a book titled Tetsudo misuteri no keifu (The Genealogy of Train Mysteries) last year and introduced many mystery stories set or focusing on trains in Japan and the United Kingdom, the birthplace of train mystery stories.

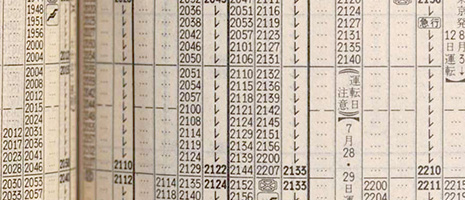

“Japanese railway timetables have been consistently accurate since the early stage of railway development. One of the remarkable characteristics of Japanese railway mystery stories is the frequent use of alibis based on such accurate timetables,” says Haraguchi. “Because it could not be said that railway timetables were very accurate in many countries prior to the acceleration of the privatization of state-owned railways in European countries, mystery stories using timetables as plot devices would not be credible. In the UK, stories based on tightly closed spaces within stations or trains were more common.”

A long novel titled Funatomike no sangeki (The Tragedy of the Funatomi), which was published in 1936 by Yu Aoi (1909–1975), was Japan’s first railway mystery story using a timetable as an alibi. Aoi was an electrical engineer influenced by British writers such as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859–1930), famous for his detective stories featuring the excellent detective Sherlock Holmes, and Freeman Wills Crofts (1879–1957), famous for his railway mystery stories, including Death of a Train. Aoi wrote detective stories as a side job.

The Tragedy of the Funatomi was about a case of the murder of the mother and the daughter of the Funatomi family, wealthy merchants in Osaka. “I actually compared a timetable used at that time with the novel and could not help getting excited at the precise plot based on a real railway timetable,” says Haraguchi. “Many writers published stories using timetables in the postwar era, but this mystery pioneered the use of timetables as a plot device.”

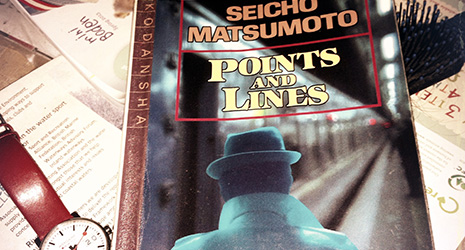

Points and Lines, published by Seicho Matsumoto (1909–1992) in 1958, was selected by Haraguchi as one of best works among many railway mystery stories published after World War II. In this novel, first published as a series in a magazine, a skeptical old police detective in cooperation with a young detective broke down the alibi of the criminal in the death of a man and woman found on the beach in Fukuoka. Matsumoto wrote this novel in Room 209 of the Tokyo Station Hotel at Tokyo Station. In the corridor outside what is now Room 2033 are hung framed pages from the first installment of the magazine series Points and Lines and the timetable of Tokyo Station at that time, the novel’s the key plot device. Points and Lines was translated into more than ten languages, including English and French, and became a major Japanese mystery novel.

“Points and Lines is notable for its elegant writing style as well as its realism,” says Haraguchi. “There are many other important writers, but I have no doubt that this novel significantly changed the course of Japanese mystery writing.”

Today railway mystery stories are not as widely published. A notable exception is Kyotaro Nishimura, who publishes at least one railway mystery story almost every year. Of the 580 novels that he has published, most are railway mystery stories. Nishimura’s first such novel was Buru torein tokkyu satsujin jiken (Blue Train Express Murder Case), which was published in 1978. This novel uses a sleeper express named Yuzuru, which was becoming popular at that time, as a plot device. Subsequently, Nishimura wrote novels set on railway lines across the country, one after another, and has already published a novel featuring the Hokkaido Shinkansen, which opened in March 2016.

“Readers can travel to unforgettable or unknown places through railway mystery stories. This is one of the attractions of the genre,” says. Haraguchi. “Novels are closely associated with the time periods in which they were written. New styles will be required for modern railway mystery stories.”

© 2009 Cabinet Office, Government of Japan