Home > Highlighting JAPAN > Highlighting Japan February 2018 > My Way

Highlighting JAPAN

Building Bridges through Poetry

Poet, man of letters and woodblock artist Peter MacMillan from Ireland circulates information about the heart of Japan through his translations of Japanese literature.

Peter MacMillan lives in Tokyo. Bamboo is planted in the bare ground at his house, which is also his atelier. When you go through the wooden gate, you can see a water harp pot.i It exudes a quiet ambience that gives the sense of a Japanese atmosphere.

MacMillan was born and raised in Dublin, Ireland. He studied literature and philosophy at the National University of Ireland and graduated at the top of his class. He came to Japan by chance in 1987, and since then he has spent thirty years here; more than half of his life.

MacMillan says with a smile on his face, “When I was 28 years old, I decided to come to Japan to work as a university lecturer. I decided to enjoy having adventures in Japan, which I knew nothing about back then.” After graduating from the National University of Ireland, MacMillan went to the United States and became a visiting researcher at Princeton University, Columbia University and the University of Oxford. At Columbia University, MacMillan studied under Professor Donald Keene, who is a Japanese literature researcher. After coming to Japan, MacMillan taught philosophy at the University of Maryland, University College, Japan School. He also taught English and British and American literature at Kyorin University and worked as a poet, publishing collections of poems.

When MacMillan was unable to decide between staying in Japan and returning to Ireland at the age of 40, he decided to translate Japanese collections of poems into English. He embarked on the English translation of One Hundred Poems by One Hundred Poetsii and published One Hundred Poets, One Poem Each in 2008. Professor Keene evaluated this work highly, and the translation won the Donald Keene Center Special Prize for the Translation of Japanese Literature and the Special Cultural Translation Prize of the Japan Society of Translators. This achievement helped MacMillan to overcome his indecision and led him to decide to be a bridge-builder between Japan and the world. Following this, in 2016, he published the English translation of The Tales of Ise, a collection of waka poems from the early Heian period (794–1185); in 2017, he published One Hundred Poets, One Poem Each. MacMillan continues his translation activity with a focus on waka, 31-syllable Japanese poems.

His activity was highly recognized and in 2017 he was invited as a translator in residence to “NIJL Arts Initiative: Innovation through the Legacy of Japanese Literature,” a project by the National Institute of Japanese Literature (NIJL) of the National Institutes for the Humanities (Inter-University Research Institute Corporation) to share Japanese classical works that have been handed down from generation to generation for more than a thousand years with researchers all over the world, which made him even more determined to be a bridge-builder between Japan and the world.

MacMillan finds it very difficult to translate Japanese and Japanese classics, such as waka, into English. It is frequently the case that waka have no subjects, and one word has multiple meanings. As a result, each poem has a complicated dual structure, which makes it extremely difficult for MacMillan to express the intentions of the poets in English. But MacMillan says, “Because waka have no subjects and are ambiguous, they enable poets to express profound emotions. This made me aware of the delicateness and attractions of the Japanese language and the attractions of waka.”

MacMillan also discovered the differences in an aesthetic sense.

He says, “Japanese people have the aesthetic sense that because beauty is short-lived and fragile, it is beautiful. Because this is completely different from the Western aesthetic sense, it was a major discovery for me.”

MacMillan’s discovery was made on the basis of the following two waka poems in The Tales of Ise, which he translated into English: Yononakani taete sakura no nakariseba, haru no kokoro wa nodoke karamashi (If there were no cherry blossoms in the world, my heart would be calmer in spring) and Chireba koso itodo sakura wa medetakere, ukiyo ni nanika hisashi karubeki (We find the cherry blossoms so beautiful because they fall. Nothing lasts eternally in this sorrowful world, does it?) The former says that in the spring, we are worried whether the cherry blossoms will bloom, and when the cherry blossoms bloom, we are worried that they will fall. The latter says that there is nothing eternal in the world, and that the cherry blossoms are wonderful because they fall.

MacMillan says, “The aesthetic sense and spirituality that you should love the world because it is short-lived and fragile still represents the spirituality of the Japanese people.”

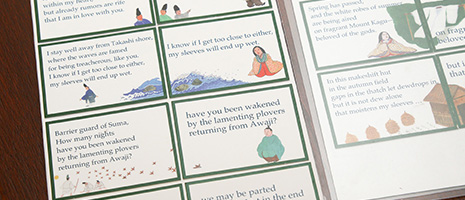

MacMillan’s efforts as a bridge-builder between Japan and the world go beyond the English translation of classical literature. He named himself “Seisai” after Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849), whom he reveres, and produces woodblocks of Shinfugaku sanju-rokkei (“Thirty-Six New Views of Mount Fuji”). He has also produced an English version of a card game called karutaiii featuring One Hundred Poems by One Hundred Poets, and organizes world competitions. In the future, MacMillan will publish the revised translation of One Hundred Poets, One Poem Each and will also publish a book about Mount Fuji, which is described in Japanese literary works from Man’yoshuiv to contemporary works. MacMillan is committed to expressing the spirituality of Japan to the world with a range of approaches.

Note

i This is a type of Japanese garden ornament that was invented in the Edo period (1603–1867). You can enjoy the echoes of the sound of water drops that drop into a hollow bowl buried underground close to a water bowl.

ii This is a collection of poems by 100 poets compiled by Fujiwara Teika (1162–1241), a major poet in the Kamakura period (1185–1333).

iii This is a card game where players divide the top part of 5-7-5-7-7 poems, 5-7-5, from the bottom part, 7-7, listen to the top part that is read aloud, receive the cards for the bottom part and compete based on the number of cards they win.

iv This is the oldest Japanese collection of waka poems, compiled in around the eighth century. It includes 4,536 poems composed by many men and women, from the Emperor to the general public.

© 2009 Cabinet Office, Government of Japan