INDEX

- English

- 日本語

- English

- 日本語

An image of the moon appearing from behind the clouds as in the poem by Fujiwara no Akisuke

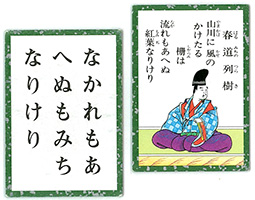

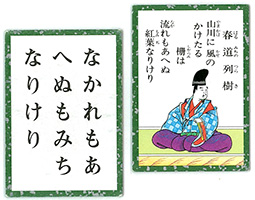

Hyakunin Isshu karuta: yomifuda card (right) and torifuda card.

October 2020

The Light of the Moon

Akikaze ni

tanabiku kumono

taema yori

moreizuru tsukino

kageno sayakesa

—Fujiwara no Akisuke (1090–1155), Hyakunin Isshu 79

Autumn breezes blow

long trailing clouds.

Through a break,

the moonlight—

so clear, so bright.

—Trans. by Peter MacMillan, One Hundred Poets, One Poem Each

In autumn, the air is clear and the moonlight (described as “tsukino kage” in waka or Japanese classical poetry) shines brightly. In writing the Japanese poem above, Fujiwara no Akisuke expresses the purity and crispness of moonlight streaming from a break in the clouds on a breezy autumn night.

According to the translator Peter MacMillan, “The Japanese have been enamored with the moon since ancient times. They are particularly fond of the autumn moon, which is the subject of this poem. However, the Japanese use of waka poetry extended beyond writing about the moon in autumn, taking in love, farewells, and every other aspect of the Japanese psyche. There are, of course, many poems about the full moon, but there are also poems written about the crescent moon or a playful moon peeking out from a veil of clouds, or even the moon that is hidden, which we must imagine in our hearts. This love of the moon is one of the unique characteristics of Japanese culture.

“In this poem, a substantive ending expresses the joy at suddenly seeing the moon emerge from the clouds; I use a dash to express this in the English translation. It is difficult to translate the sense of the Japanese word sayakesa into English. I have translated it as “so clear, so bright” but in Japanese it has connotations of elegant spiritual purity as well.

“Because there are countless descriptions of the moon in classical Japanese literature, I sometimes feel that instead of being called the “Land of the Rising Sun,” Japan should be called the ‘Land of the Beautiful Moon.’”

Hyakunin Isshu (One Hundred Poets, One Poem Each)

In his later life, medieval poet Fujiwara no Teika (also known as Fujiwara no Sadaie) selected one poem by each of 100 celebrated poets and compiled the One Hundred Poets, One Poem Each (Hyakunin Isshu), the most popular anthology of waka in Japan.* This collection of poems—also referred to as the Ogura Hyakunin Isshu—is said to have been selected by Teika at a retreat at the foot of Mount Ogura in Kyoto. The poems in the collection were turned into a set of karuta playing cards that divides the waka into the first part, or kaminoku (the first three lines with a 5-7-5 syllable pattern), and the second part, or shimonoku (the last two lines with a 7-7 syllable pattern). As the first part of the poem (the yomifuda or “reading card,” with the whole poem on it) is read aloud, players compete with each other to find the matching ending of the poem (torifuda card). Even today this card game is still played by many people.

Peter MacMillan is one of many fascinated by the Hyakunin Isshu. He has published One Hundred Poets, One Poem Each and has also produced an English version of Hyakunin Isshu karuta titled WHACK A WAKA. Based on his strong belief that the Hyakunin Isshu represents the heart of the Japanese people, MacMillan also organizes karuta competitions around the world and hopes that the card game will one day become an Olympic event. (See the February 2018 issue of Highlighting JAPAN.)

* The Japanese anthologies of waka poetry include the oldest anthology, the Manyoshu, compiled in the middle of the eighth century; the twenty-one Chokusen wakashu, and private collections of waka poems compiled by a single editor (poet). Chokusen wakashu are anthologies of superior waka poems produced at the Japanese court collected by imperial command in a series of compilations such as Kokin wakashu and Shin kokin wakashu, and dating from the early tenth century to the middle of the fifteenth century.