September 2022

- PREVIOUS

- NEXT

Masaoka Shiki: A Poet Who Brought Innovation to Haiku

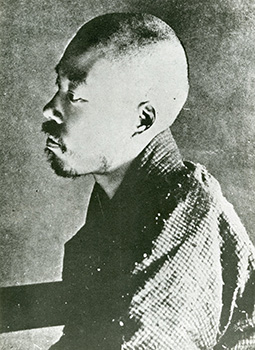

Masaoka Shiki

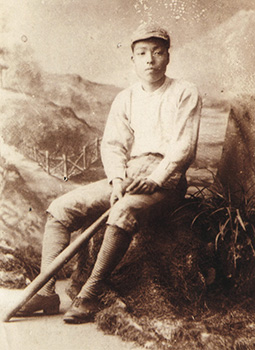

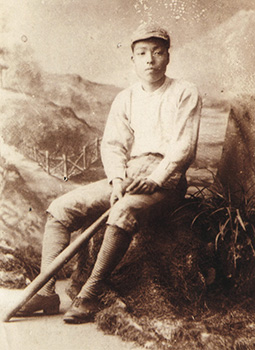

Shiki in a baseball uniform, taken when he was 23

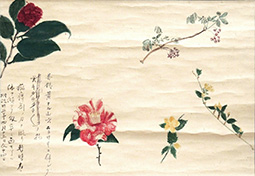

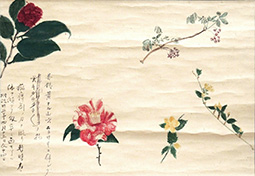

A sketch of a flower drawn by Shiki in 1902, just before his death (Collection of the Shiki Museum)

Masaoka Shiki (1867–1902) brought innovation to the world of haiku poetry during the Meiji period (1868–1912) while also carrying on its traditions. He left the world many haiku poems that “sketch from life,” capturing nature and other things just as they are.

Masaoka Shiki (hereinafter, “Shiki”) was born in 1867 in what is now Matsuyama, Ehime Prefecture. He left behind a legacy of haiku poems, essays, critiques, and more in a variety of genres, and he is one of the leading literary figures of the Meiji period. Shiki passed away at the young age of 34, but his influence on the world of haiku in particular during his short life is immeasurable.

He began creating haiku at the age of 18, and from his early 20s, while also composing his own, he became engrossed in the sorting of haiku, collecting many haiku from the past. This research would lead to his innovations in haiku.

“Through steady research requiring time and effort, Shiki considered the path haiku should take in the future and collected his own thoughts on haiku,” says Hiraoka Eiji, curator of the Shiki Museum in Matsuyama. “With Basho Zodan (Some Remarks on Basho), released in 1893 when he was 26, he criticized the admiration of great haiku poet Matsuo Basho* in haiku circles, and this had a great impact on the world of haiku at that time.”

While Shiki highly praised Basho’s style of poetry ripe with poetic inspiration, he also pointed out its shortcomings. He was also criticizing the poets of his day who had deified Basho, this accounting for their lack of fresh ideas, their use of only formulaic language, and their rehashing of past haiku. In the opening of Haikai Taiyo (The Elements of Haiku), released in 1895 when Shiki was 28, he writes that “haiku is a part of literature. Literature is a part of art. This means the standard of beauty is the standard of literature. The standard of literature is the standard of haiku. In other words, paintings, sculptures, music, theater, poems, and novels should all be critiqued according to the same standard.”

Additionally, Shiki insisted that to create haiku of literary merit, one should express one’s own emotions by sketching nature and other things just as they are.

This insistence was influenced by the idea of sketching from life in Western arts, which had been introduced to Japan from Europe during the Meiji period. Shiki also recommended the use of modern things as themes and language not used in conventional haiku. For example, he composed haiku based on baseball, a new sport that had spread in Japan, having come from the United States during the Meiji period.

Hiraoka says, “Shiki probably thought that haiku should be able to rank with other literature and art from the West. He is recognized as having started a movement of haiku innovation, which caused haiku to be reborn as a form of modern literature.”

His innovations in haiku caused a great sensation, and many people came to gather around Shiki seeking his teaching. He contracted pulmonary tuberculosis and was in his sick bed from age 29 in 1896, yet he fully supported the haiku magazine Hototogisu that his friend published in Matsuyama in 1897. After the publishing office moved to Tokyo, this magazine greatly influenced the world of haiku.

Shiki created around 25,000 haiku poems in his lifetime, and he continued to compose poems right up until his death. “The garden flowers seen from his bed at home and the personal items arranged near his bedside came to be important themes for his haiku. One cannot ignore this time spent in his sick bed when considering his haiku,” says Hiraoka. “Many friends and acquaintances constantly visited while Shiki was in his sick bed at home, and from this, we can see that he was a person full of charm,”

Shiki brought innovation to haiku and established the poetic form as modern literature. His achievements are still acclaimed.

* See Highlighting Japan May 2022, “Matsuo Basho: The Unparalleled Haiku Poet” https://www.gov-online.go.jp/eng/publicity/book/hlj/html/202205/202205_12_en.html

natsukusa ya

besu boru no

hito toshi

summer grass

baseball players far off

in the distance

—Translation by Cor van den Heuvel and Nanae Tamura, Baseball Haiku: W. W. Norton & Company, 2007

Composed in 1898 at the age of 31. Natsukusa (summer grass) is the kigo (seasonal word) for summer. Shiki, who loved baseball, created some haiku about it. The haiku speaks of a scene where one can see the people playing baseball on the far side of the summer grass. When this haiku was created. Shiki’s illness had progressed to the point that it was difficult for him to walk, and it is thought that from his sick bed, he was thinking of a baseball game he had seen at some point.

kaki kueba

kane ga narunari

Horyuji

I bite into a persimmon

and a bell resounds—

Horyuji

—Translation by Janine Beichman, Masaoka Shiki: Kodansha International, 1986

Composed in 1985 at the age of 28. Kaki (persimmon) is the kigo for autumn. This is the most well-known of Shiki’s haiku. He created the haiku in Nara, while on his way back to Tokyo from his convalescence in his hometown of Matsuyama. It paints a scene of someone taking a break while eating a persimmon at a tea house in Nara one autumn day, and just then, the sound of a bell at Horyuji Temple can be heard. Within this single haiku, he vividly expresses sight, taste, and sound with the orange color and sweet taste of persimmons, which he loved, and the sound of an echoing temple bell.

ikutabi mo

yuki no fukasa o

tazunekeri

again and again

I ask how high

the snow is

—Translation by Janine Beichman, Masaoka Shiki: Kodansha International, 1986

Composed in 1986 at the age of 29. Yuki (snow) is the kigo for winter. Shiki had already fallen ill at this point, and in this haiku, he asks those around him over and over how much snow has fallen after hearing that it was snowing outside. He was unable to get up and see the snow piling up, and in his mind as he lay in his sickbed, the snow may have accumulated quite a bit.

- PREVIOUS

- NEXT